How to Introduce Dogs When One Is Reactive: A Safe, Step-by-Step Guide

Introducing two dogs is stressful enough, and when one of them is reactive, the pressure skyrockets. Many owners worry about fights, setbacks, or making the reactivity worse. The good news? With the right structure, the right pace, and the right environment, reactive dogs can successfully meet new dogs and even build positive associations.

This guide walks you through the safest, trainer-approved steps for introducing dogs when one struggles with reactivity, especially in a busy city like Chicago.

What Reactivity Actually Means

Reactivity is one of the most misunderstood behavior challenges in dogs. People often label reactive dogs as “aggressive,” “dominant,” or “bad with other dogs,” when in reality, most reactive behaviors are rooted in big feelings — fear, uncertainty, frustration, or overexcitement.

A reactive dog isn’t trying to be difficult. They’re communicating the only way they know how.

Common reasons dogs become reactive include:

Feeling unsafe or unsure around other dogs

Frustration when they can’t greet

Past negative experiences with unfamiliar dogs

Overarousal and difficulty regulating emotions

Protective feelings toward their guardian or environment

Reactivity is not a personality trait — it’s an emotional response shaped by experience, genetics, and environment.

Common types of reactivity:

Fear-based reactivity: The dog wants distance and safety.

Frustration-based reactivity: The dog wants to greet but can’t manage the emotional intensity.

Overarousal: Too much energy, too fast.

Barrier frustration: Being behind a leash, gate, or window increases tension.

With thoughtful structure and training, most reactive dogs can build the skills needed to coexist peacefully with others, even if they never become highly social “dog park dogs.”

Before You Even Think About an Introduction, Evaluate.

If one dog is reactive, you’ll want to set the stage carefully before the dogs ever see each other. Rushing this part is one of the top reasons introductions go poorly.

Management Comes First

Your reactive dog should have the tools, space, and support needed to stay under threshold. This often means:

Starting with distance

Using neutral spaces

Keeping leashes loose

Avoiding crowded or unpredictable environments

Know Your Dog’s Threshold

A dog’s threshold is the point where they can no longer think, listen, or process. Your goal is to keep both dogs below threshold.

Signs a dog is nearing threshold:

Stiffening

Staring

Holding breath

Ignoring cues

Barking, lunging, whining

If your reactive dog can’t recover within 10–20 seconds after seeing another dog at a distance, they’re not ready for introductions yet. Work on foundational skills and emotional regulation first.

Before the Meeting, Decide Whether the Dogs Are Actually Compatible

Not all dogs are meant to be friends, and that’s okay! As humans, we certainly don’t like everyone we meet. Some dogs simply prefer space, neutrality, and predictability over being friends with other dogs.

Questions to ask yourself before the meet and greet:

Does your dog enjoy other dogs, or merely tolerate them?

Has your dog shown any bite history or escalated reactions?

Can both dogs walk past each other at a distance without distress?

Are both owners aligned on structure, pacing, and safety?

If you’re unsure, it’s always better to go slow or consult a trainer.

Then, Choose the Right Location for Reactivity-Friendly Introduction

Preparing the environment and having a plan can make the experience smoother for both dogs.

Location makes or breaks the introduction. Avoid tight spaces such as:

narrow sidewalks

small apartment hallways

elevator lobbies

dog parks

small backyards

Ideal starting locations include:

quiet residential side streets

large parks during low-traffic hours

school fields

spacious parking lots

These give you room to adjust distance quickly.

The Introduction Plan at a Glance

To keep both dogs safe and regulated, follow a simple, predictable flow:

Visual exposure at a distance — dogs see each other but don’t interact.

Parallel walking — slow and structured.

Curved approach, quick sniff-and-go — no direct, head-on greetings.

Indoor coexistence with barriers — baby gate separation.

Supervised off-leash time — only after sustained calmness.

Post-intro relaxation — this is just as important

Phases can take minutes, hours, or multiple sessions — every dog moves at a different pace.

1. Visual Exposure at a Distance

Reactivity Is About Safety, Not Manners

A reactive dog isn’t being stubborn; they’re responding to fear, frustration, or overwhelm. Before introducing dogs, your first goal is to create enough distance that the reactive dog can notice the other dog without going over threshold.

Signs you have enough distance and your dog is comortable:

Soft body language

Able to take treats

Able to disengage without staring

No vocalizing or lunging

Signs your dog isn’t ready to move closer:

Stiff posture

Lunging

Fixation

Slow recovery

Whining or screaming

If you see any of those, pause the process. You’ll need more foundational work first.

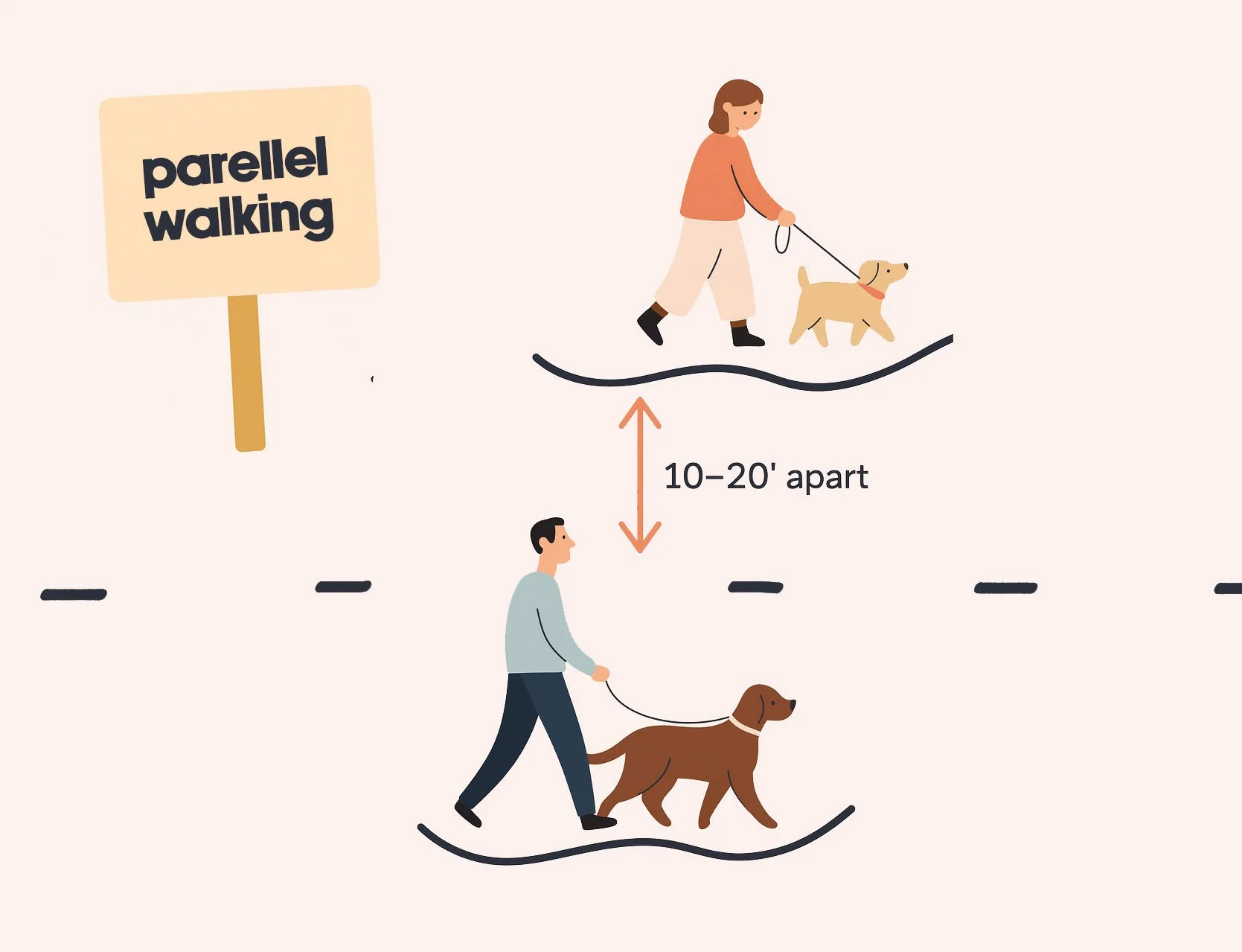

2. Parallel Walking

Parallel walking lets both dogs see each other without direct pressure. Neither dog needs to interact — they just coexist while moving forward. Movement helps reduce tension and gives both dogs something to “do” rather than stare, and if you’re unsure how close to walk or how to manage the leash pressure, working with a pet trainer in Chicago can help guide you through the setup safely.

How to set up a parallel walk

Start 20–40 feet apart

Walk in the same direction

Reward your dog each time they look calmly

Slowly decrease distance only if both dogs stay relaxed

This is not a race to get the dogs close together. It’s about building comfort. Most owners walk too slowly or too close during a parallel walk. The goal is forward momentum — movement diffuses pressure and helps prevent fixation.

Look for Positive Body Language Before Moving Closer

Reactivity won’t disappear instantly. Instead, we watch for small shifts:

dog sniffing the ground

soft eyes

loose tail movement

choosing to disengage on their own

taking treats consistently

curved body language

These micro-signals tell us we’re in the learning zone. If you see signs of overwhelm — stiffening, freezing, staring, barking — increase distance immediately.

Signs you need more distance

Staring or freezing

Tail high and tight

Quick, sharp movements

Vocalizing

Pulling toward or away

You’re looking for “green light moments” — tiny signals that the reactive dog is curious but not overwhelmed. These glimmers tell you the emotional environment is safe to proceed.

3. The First Real Greeting

Some dogs will never need (or want) a close-up greeting. Coexistence is still a win. But if both dogs appear relaxed, you can attempt a quick 3-second greeting.

The 3-Second Rule

Allow the dogs to sniff briefly.

Count to three.

Cheerfully call them away.

Walk a few steps to reset.

Short, controlled interactions prevent misunderstandings and give both dogs a confidence boost.

Many introductions go wrong because owners allow:

head-on greetings

prolonged sniffing

tight leashes

face-to-face pressure

A safer greeting looks like:

a loose, curved approach

Brief sniffing

gentle interruption (“this way!”)

immediate movement apart

Short, controlled, and low-pressure. Skip greetings entirely if either dog is stiff, frozen, or hyper-focused. There is no benefit to forcing contact, neutrality is safer and healthier.

4. Indoor Coexistence with Barriers

What works outdoors does not translate indoors. Walls, tight spaces, and resources can spike arousal quickly.

Common mistakes indoors:

Letting the dogs roam freely too soon

Having toys, bones, food bowls, or beds accessible

Introducing in tight doorways or hallways

Allowing long or intense sniff sessions

Instead, keep sessions short, structured, and supported with barriers.

Baby gates, pens, and leashes aren’t like training wheels — they’re safety tools that create predictability and reduce the risk of conflict inside the home.

5. Supervised Off-Leash Time

Even though the dogs are “off-leash,” both should wear drag leashes (lightweight 4–6 foot leashes with no looped handle). Drag lines give you a quiet, hands-off way to intervene if:

play becomes too intense

one dog becomes fixated

body language shifts into discomfort

you need to calmly separate them

This prevents grabbing collars (a common trigger for redirected aggression) and keeps things smooth if either dog suddenly needs space.

PRO TIP: Keep Sessions Short and Structured

Off-leash intros are not “set it and forget it.” They should be short bursts of interaction, intentionally paused before things get too exciting.

Think of it like interval training:

Let the dogs play or explore together for 10–20 seconds.

Call them apart for a reset — a short sniff break, a walking lap, or a scatter feed.

Resume only if both dogs look loose and wiggly.

These tiny breaks prevent overarousal, allow emotional resets, and help both dogs stay regulated.

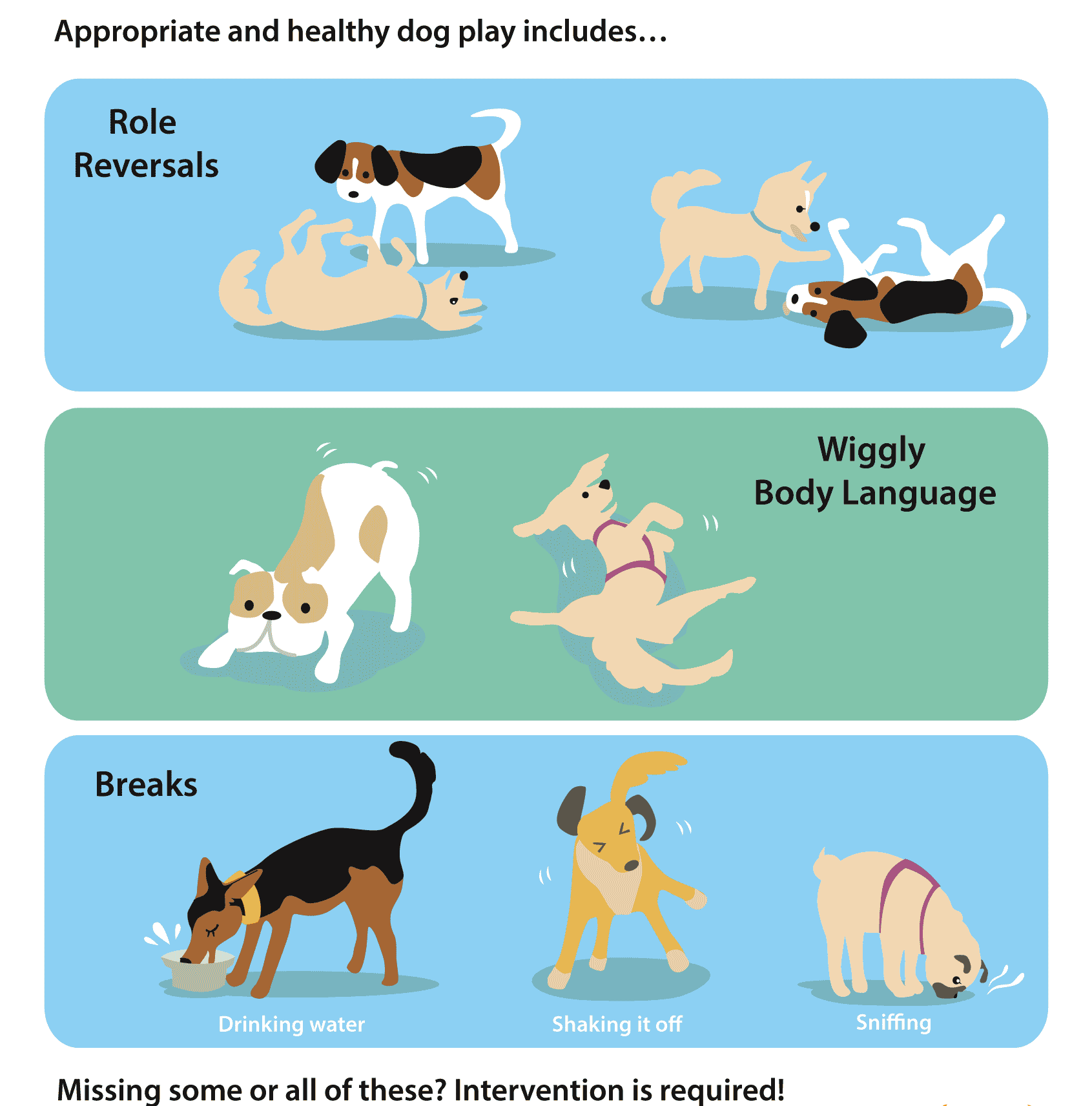

PRO TIP: Watch for Healthy vs. Unhealthy Play

You’re looking for:

bouncy movements

self-handicapping

loose bodies

taking turns chasing or wrestling

frequent natural breaks

You’ll want to interrupt if you see:

humping

pinning

mounting that doesn’t stop

one-sided or nonstop chasing

vocalizations that sound distressed rather than playful

stillness or freezing

intense staring

Shorter, well-regulated sessions are far safer (and more successful long-term) than one long, chaotic play session.

End While Things Are Going Well!

Reactive dogs do best when off-leash time ends before emotions peak. Wrap the session while both dogs feel confident, relaxed, and successful. Ending on a good note teaches the reactive dog that being around another dog is safe, predictable, and not overwhelming.

6. Post-Intro Relaxation

Even if the greeting goes beautifully, the emotional aftermath is just as important.

What to do after the dogs meet:

Take the reactive dog on a decompression walk

Give both dogs downtime, not more social time

Keep intros short and sweet for the next few days

Avoid high-stakes situations too quickly

Many reactive dogs struggle after the event due to adrenaline. Watch for delayed stress signals like pacing, panting, scanning, or sudden clinginess; these tell you the dog needs more decompression.

Common Mistakes to Avoid with Reactive Dogs

Avoid these at all costs:

letting dogs greet on tight leashes

allowing tense face-to-face moments

trying greetings in your hallway or doorway

forcing eye contact

keeping interactions going too long

adding pressure by saying “be nice!” or “say hi!”

The safest intros are short, structured, and optional.

When to Involve a Trainer

A reactive dog meeting a new dog is one of the highest-risk situations for reactivity setbacks. A trainer can read early warning signals, manage distance, and prevent mistakes you may not realize you’re making — especially if you’re working in busy neighborhoods like Lincoln Park. You can also explore local options for dog training in Lincoln Park if you need location-specific support.

Bring in a trainer if:

your dog has a history of growling/lunging

you’re introducing a dog to a new household member

both dogs are nervous

you want professional control of distance

you want help reading early warning signals

A good trainer prevents mistakes you may not even realize are happening.

Final Thoughts

Introducing dogs when one is reactive requires patience, structure, and compassion. Your dog isn’t trying to give you a hard time — they’re having a hard time. Every step you take to reduce pressure, create space, and build emotional safety helps your dog feel more confident around other dogs.

Whether the goal is friendship, tolerance, or simply peaceful coexistence, thoughtful introductions make all the difference.

And remember: Success doesn’t always look like play. Sometimes the biggest win for a reactive dog is simply walking calmly near another dog without worry. That is progress, and it’s worth celebrating.

Frequently Asked

Q: Can a reactive dog learn to like other dogs?

Yes! With slow introductions, distance control, and positive associations, many reactive dogs can learn to tolerate or even enjoy certain dogs.

Q: Should reactive dogs meet other dogs on a leash?

Only if leashes are kept loose. Tight leashes add tension and can trigger reactivity during greetings.

Q: Can I introduce my reactive dog at home?

Avoid in-home introductions until the dogs have met in neutral locations with success. Indoor spaces add pressure.

Q: How long should the first meeting last?

A few seconds. Short, structured greetings prevent overwhelm and help build positive experiences.

Q: What if my reactive dog barks immediately?

Increase distance. Barking means the dog feels unsafe. Return to parallel walking.

Q: Should reactive dogs go to dog parks for socialization?

No. Dog parks overwhelm reactive dogs and often worsen behavior.

Q: What’s the safest way to continue building the relationship?

Alternate between parallel walks, short sniffing sessions, and separation with movement between each interaction.

Explore My Services

Puppy Training | Obedience Training | Reactivity Training | Behavior Modification | Puppy Board & Train

Questions about private training, process, or board and train? Reach out!