How to Introduce a Puppy to a Reactive Dog

Bringing a puppy into a home with a reactive dog can feel ambitious. If you’re already navigating reactivity with another dog, this is very much a slow-and-steady situation—and that’s exactly how we approach it in our reactivity training.

It’s not impossible, it’s just something that needs a plan, patience, and a lot of management up front.

Puppies are chaotic. Reactive dogs thrive on predictability. Our job is to make those two worlds coexist without anyone melting down.

This guide walks through how to do introductions thoughtfully, what not to rush, and how to set both dogs up for long‑term success.

First, a quick level set

A puppy won’t “fix” a reactive dog. And a reactive dog won’t magically tolerate puppy behavior just because the puppy is small or cute.

Reactivity is about emotional responses (often fear, frustration, or over‑arousal), not obedience.

It’s also worth knowing that puppies go through normal fear periods. During these phases, new experiences can feel extra big.

A single interaction that’s overwhelming or confusing can stick longer than you’d expect.

That doesn’t mean one mistake ruins everything. It just means slower, calmer introductions really matter.

The goal here isn’t instant friendship. It’s easy, low‑key coexistence.

Step 1: Separate living spaces (yes, even if you feel bad)

Before the dogs ever meet, set up the house so they cannot rehearse bad interactions.

That usually means:

Crates in separate areas

Closed doors

Each dog should have:

Their own resting area

Their own feeding space (this one is extra important)

Time where they’re not being watched closely by the other dog

This kind of setup is especially important in multi‑dog households, where small moments add up quickly. Thoughtful management now prevents bigger problems later (and keeps everyone’s stress lower). I

f this is new territory, our multi‑dog household training page breaks down how to structure shared spaces.

Management isn’t a failure! It’s what keeps everyone under threshold and safe.

Step 2: Start with scent, not face‑to‑face

Dogs learn a lot before they ever see each other—and for both reactive dogs and puppies, that’s a good thing.

Face‑to‑face greetings look polite to humans, but to dogs they’re actually rude.

Nose‑to‑nose, eyes locked, bodies squared up—there’s very little space, choice, or time to process what’s happening. For a reactive dog, that pressure can tip into a reaction. For a puppy in a fear period, it can be overwhelming before they even know how to respond.

In natural dog communication, greetings are usually:

Curved, not straight on

Side‑by‑side or slightly offset

Brief, then broken off

That quick sniff and disengage matters. It lets dogs gather information without getting stuck in an interaction that feels like too much.

Starting with scent and indirect exposure keeps things calmer and more predictable.

Try:

Letting the reactive dog sniff items the puppy has slept on

Walking them separately in the same neighborhood (different times, same routes)

Swapping spaces briefly so each dog can investigate without pressure

This gives both dogs information without intensity, and avoids forcing greetings that neither dog is ready for yet.

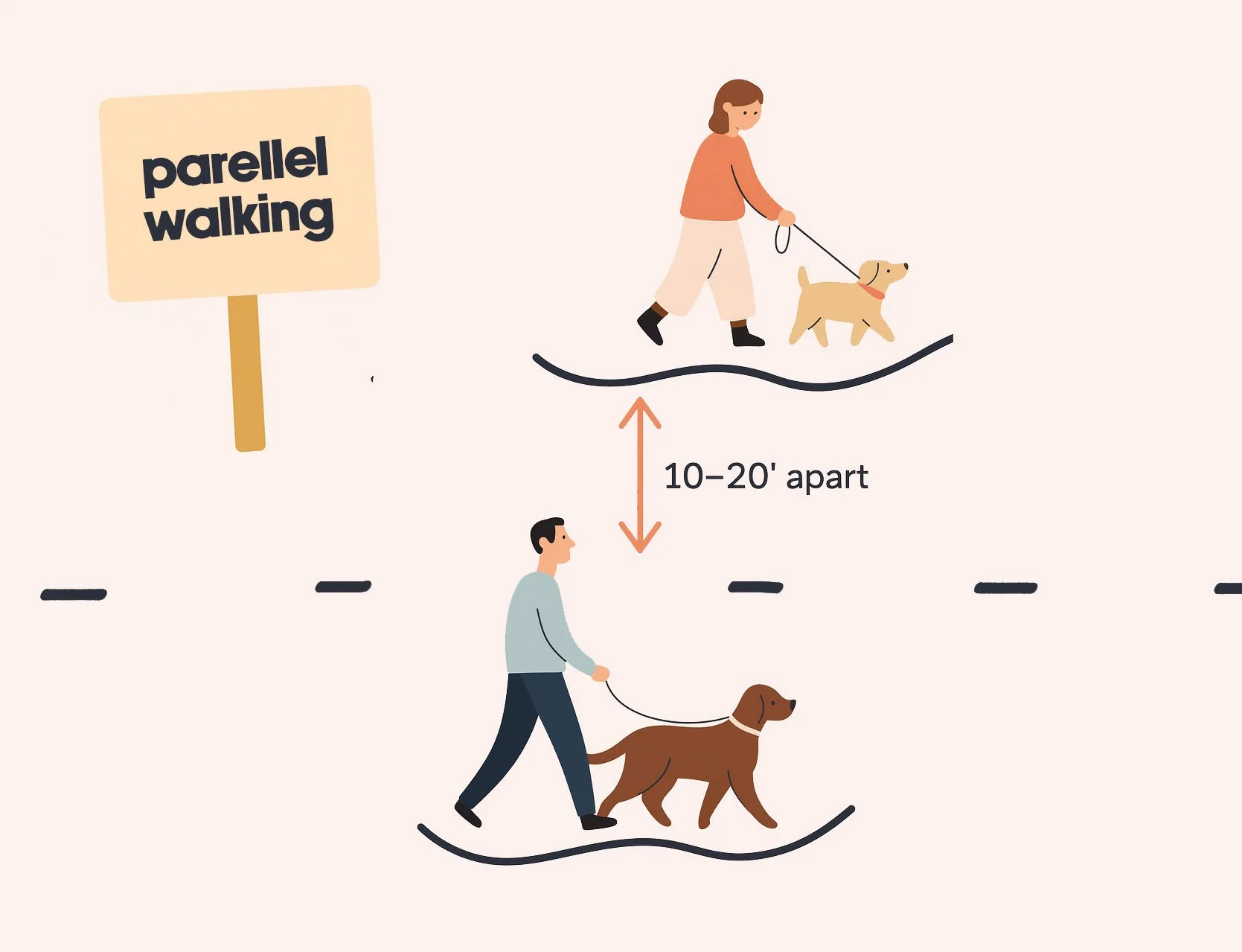

Step 3: Parallel exposure (the gold standard)

The first visual introductions should be at a distance where the reactive dog can:

Notice the puppy

Stay relaxed

Disengage easily

Think:

Parallel walks with plenty of space

Puppy behind a gate while the reactive dog moves freely

Both dogs on leash, not approaching

If the reactive dog is stiff, vocal, fixated, or unable to eat—you’re too close.

Step 4: Short, boring interactions (this is a good thing)

When you do allow closer interactions, keep in mind that puppies are still learning how the world works—and reactive dogs already find the world a little loud.

Short, structured interactions help everyone stay comfortable.

That usually looks like:

Brief check‑ins

Loose leashes or drag lines

Ending the interaction before either dog gets overwhelmed

You’re watching for:

Sniff and disengage

Loose, relaxed movement

Curiosity without intensity

No wrestling marathons. No cornering. No pressure to “be friends.”

If it feels boring, you’re doing it right.

Step 5: Teach the puppy manners early

Puppies don’t come with impulse control. You have to teach impulse control and how to be calm.

Priority skills to teach your puppy:

Name response (name game)

Recall away from the other dog (touch cue)

Settling on a mat (place)

Leaving the reactive dog alone when asked (leave it)

Every time the puppy rehearses pestering, the reactive dog’s tolerance drops.

Step 6: Advocate hard for the reactive dog

Your reactive dog didn’t ask for a puppy. Make sure your reactive dog gets:

One‑on‑one time with you

Walks without the puppy

Breaks from interaction

Predictable routines

Because a dog who feels safe and heard copes better.

Common mistakes to avoid

These are all very understandable—and very common:

Moving too fast because the puppy is young and “needs socialization”

Assuming puppies will bounce back from stressful moments

Letting the puppy repeatedly pester the reactive dog

Scolding the reactive dog for growling or asking for space

Dropping management once things seem okay

A lot of adult dogs who struggle socially didn’t lack exposure—they just needed more support during it.

When to bring in professional help

If you’re seeing:

Lunging or snapping

Prolonged fixation

Resource guarding between dogs

Escalating stress signals

…it’s time for support.

Introducing a puppy to a reactive dog is very situational. Having a trainer who can see the layout of your home, read both dogs in real time, and adjust the plan makes a big difference. This is exactly the kind of case we handle in private dog training sessions.

Final thoughts

Introducing a puppy to a reactive dog can feel like a lot, and that’s because it is a lot. You’re balancing two very different nervous systems and trying to keep everyone feeling safe.

Slow, thoughtful introductions protect your reactive dog’s comfort and help your puppy build good feelings about other dogs.

Take your time. Keep things uneventful. End interactions on a good note.

Calm coexistence isn’t boring—it’s the foundation everything else is built on.

FAQs

Q: Can a reactive dog ever enjoy living with a puppy?

It depends on the dog and the type of reactivity. For many dogs, tolerance comes first and enjoyment comes later. What we’re aiming for is neutrality.

Q: Is my puppy missing out on socialization if we go this slow?

No. Safe, positive experiences matter far more than lots of exposure—especially during fear periods.

Q: What if my reactive dog growls at the puppy?

That’s communication. It’s a sign to add space or structure, not a reason to punish.

Q: How long does this usually take?

Anywhere from weeks to months. Slow and steady tends to hold up best.

Q: Should I ever let them work it out on their own?

Both puppies and reactive dogs do better when humans help set the pace.